A History of Auscultation

- V. A. Cyr

- Aug 14, 2024

- 22 min read

Updated: Aug 22, 2024

The nursing process has five steps: assessment, diagnosis, planning, implementation, and evaluation. Health assessment consists of subjective and objective data. Subjective findings are the symptoms the patient is experiencing and are usually qualitative (i.e., storytelling). Objective findings are what the nurse is observing and quantitative data (i.e., numbers).

Auscultation is a technique nurses use to properly assess the patient. This is used along with other techniques (palpation, percussion, etc.) and equipment (e.g., to measure blood pressure). These will be further discussed in future posts. We have all seen healthcare workers in the hospital or actors on television wearing stethoscopes around their necks. The stethoscope has become a symbol of healthcare, but where does it come from, and how is it used?

Note: The diagrams used in this post show the front views of the organs. When discussing the sides of the organs, we will be using the terms right and left in the patient’s orientation, not the image. For example, the right lung is on the patient’s right side but will appear on the left side of the image.

Definition

Auscultation is the act of listening to internal body sounds, usually using a stethoscope. The word auscultation comes from the Latin word auscultare, meaning “to listen” (Wikipedia, 2024).

Types

There are two types of auscultation: immediate and mediate. There is also auscultation done with a Doppler ultrasound machine.

Immediate Auscultation

Immediate auscultation is the process of applying one’s ears onto someone’s body to listen to the internal organs. Doctors originally did this to listen to their patient’s heart sounds. This technique posed many problems as patients were sometimes too obese for the doctors to hear anything past the fat layers within the skin (Roguin, 2006). Some doctors chose not to do this as some patients did not frequently bathe, or the women patients refused to have a male doctor press their ear to their chest (Roguin, 2006). Immediate auscultation is not a term used today, as this technique is no longer best practice.

Mediate Auscultation

Mediate auscultation is the act of listening to the organs with a tool, such as a stethoscope. This will be more fully explored in the following sections. The term auscultation used in the following sections will refer to mediate auscultation.

Doppler Auscultation

This type of auscultation uses the Doppler ultrasound machine to hear the sounds of the venus system. This is most commonly used during pregnancy to monitor the fetal heartbeat. This method will not be discussed in this post.

History of Auscultation

Origins

René Laënnac, a French physician and musician, was the first to use the term auscultation in 1816 (Roguin, 2006). Laënnac studied the clinical assessment of the lungs using a stethoscope and was able to diagnose chest disorders (e.g., pneumonia, pleurisy, emphysema, etc.) (Roguin, 2006). Laënnac used a rolled piece of paper on his patient’s chest and found that sounds could be more easily heard and amplified with mediate auscultation (Choudry et al., 2022). He then created a hollow wooden tube to auscultate the chest easier.

Laënnac’s original drawing of the stethoscope contained multiple pieces for easy travel (Roguin, 2006).

Stethoscopes

The word stethoscope comes from the Greek words stethos, meaning “chest,” and skopein, meaning “to explore” (Roguin, 2006). A stethoscope is a medical tool with a chest piece attached to a tube connected to an earpiece. The chest piece is placed on the patient’s body in the area where the medical professional wants to listen to the organs (e.g., the chest for heart auscultation). Modern stethoscopes come in a variety of styles and for different uses. The chest pieces can be of different shapes and types for specified auscultation (e.g., cardiac, pediatric, etc.). They can have either one or two tubes that connect to the earpieces. Some even have two chest pieces to compare the sounds from two different locations and are called stethophones. The combination chest piece’s invention created two parts: the diaphragm and the bell. The diaphragm is used to auscultate lung and bowel sounds, while the bell is better for heart sounds as it can better detect lower frequencies. Stethoscopes that intensify the sounds are called phonendoscopes. Modern stethoscopes are binaural, meaning there are two earpieces or one for each ear. The first stethoscope made by Laënnac could only be used with one ear. Electronic stethoscopes are also now used in specialty practices. Stethoscopes have had many improvements throughout history, as seen in the timeline below.

Timeline Through History: The Stethescope

Uses in Medicine

Auscultation of the Lungs

Anatomy and Physiology of the Lungs

As a breath is inhaled, the air passes from the mouth and nose, past the pharynx and larynx (throat), through the trachea, into either the right or left bronchus and into the right or left lungs. Once inside the lungs, the air passes into the bronchioles and the alveoli for gas exchange with the capillaries (i.e., oxygen is swapped for carbon dioxide in the blood). When exhaling, the air takes the opposite route to exit the mouth and nose. The lungs are two organs on either side of the body, with five separate lobes. There are three lobes in the right lung: the upper, middle, and lower lobes. There are two lobes in the left lung: the upper and lower lobes.

Diagram of the anatomy of the lungs (Pokusai, n.d.).

Location of Auscultation

The lungs are auscultated anteriorly on the chest and posteriorly on the back of the patient. The thoracic cage (ribs) and clavicle (collarbone) cover the lungs anteriorly, and the thoracic cage and scapula (shoulder blade) posteriorly. Therefore, the stethoscope must be placed in the intercostal (between the ribs) spaces to hear lung sounds. Auscultation of the lungs is to assess for adventitious or extra noises during inhalation and exhalation. This would be an important piece of the assessment in patients with lung disorders and post-operatively.

The points of auscultation for the front (anterior) and back (posterior) (Ekomaru, 2020).

The numbers indicate the sequence in which the lungs are auscultated to verify their similarities or differences bilaterally. The location of numbers one (1) and two (2) will auscultate the upper lobes of the lungs. Number three (3) auscultates the middle of both lungs. Numbers four (4) and five (5) on the right lung will auscultate the middle lobe, while this will auscultate the upper portion of the lower lobe on the left lung. The middle lobe of the right lung cannot be auscultated from the back. Location number six (6) anteriorly will auscultate the lower lobe of both lungs. Location seven (7) on the posterior is to auscultate the bottom of each lung or costphrenic angle (the area where the lungs meet the anatomical diaphragm).

Normal Lung Sounds

The lungs should be asucultated during inspiration and expiration in all areas. While at rest, the average adult breathes between 10 and 20 times in one minute. Children breathe faster, approximately between 20 and 30 breaths per minute.

Tracheal sounds are heard over the trachea and sound loud and harsh (Bohadana et al., 2014).

Vesicular sounds are heard throughout most of the lungs. They are soft and sound like air blowing gently (Bohadana et al., 2014). Auscultation of vesicular noises can be heard in locations 2, 3, 4, and 6 on the diagram above.

Bronchial sounds are heard over the bronchi in the anterior chest. They are higher in pitch and sound more tubular than vesicular sounds (Bohadana et al., 2014). These can be heard on the front location 1 on the diagram.

Bronchovesicular sounds are heard in the posterior chest between the vertebrae of the spinal cord and the scapulae (Bohadana et al., 2014). In the diagram above, these sounds can be heard over locations 1 and 2 anteriorly and 3 and 4 posteriorly.

Abnormal Lung Sounds

As the body is being exerted (e.g., during exercise), it will adapt to the oxygen needs of the organs and increase the respiratory rate. Sometimes adventitious noises are only heard upon exertion (e.g., exercise induced asthma) or only during certain pahses of thebreathe. This is why it is important to listen to both the inhalation and expiration.

Wheezing sounds like a wheeze and can occur in the inhalation or exhalation phase. This is common in diagnoses of asthma or lower airway obstruction (Bohadana et al., 2014).

An airway obstruction is anything in the path of the airflow. Lower obstructions occur within the trachea, bronchi, and bronchioles. Obstructions can be partial or complete, depending on how much can be inhaled or exhaled. Some causes include infection (e.g., respiratory syncytial virus), disorders (e.g., asthma), and syndromes (e.g., aspiration syndrome) (Grover et al., 2011).

Asthma is a condition in which the bronchioles become inflamed, the muscles tighten, and extra mucus is produced, inhibiting airflow. Wheezes can be heard upon expiration with auscultation and sometimes audibly without a stethoscope.

Stridor is a high-pitched musical sound caused by an obstruction in the upper respiratory tract (Bohadana et al., 2014).

Upper respiratory obstructions occur in the nasal passage, larynx, and pharynx. These can be acute or chronic. Acute obstruction can occur due to aspiration of a foreign body, which is common in children. Chronic obstruction can occur as a result of infections (e.g., streptococcal infection), inflammation (e.g., anaphylaxis, tumour growth), or trauma (e.g., deviated septum) (Brady & Burns, 2023).

Fine crackles, or rales, are high-pitched noises in the lung base (Bohadana et al., 2014). This indicates the lungs are filled with fluid or have an infection, such as pneumonia, congestive heart failure, or atelectasis.

Pneumonia is an inflammatory process of the alveoli in one or both lungs. An infection in the lungs causes pnemonia. Infections can be from streptococcal bacteria or a complication of other lung diseases, like cancer and cystic fibrosis. Since infection causes inflammation and fluid retention, auscultation will result in crackle noises.

Congestive heart failure, or heart failure, is a syndrome that affects the heart’s ability to pump blood. Heart failure can occur on the right or left side of the heart. If the left side of the heart fails, fluid will back up into the lungs, and crackles will be heard during auscultation.

Atelectasis is when the alveoli collapse and cannot complete gas exchange. It commonly occurs after surgical procedures with anesthesia, so it is important to use spirometry and breathing exercises post-operatively to ensure proper oxygen exchange. Prolonged bed rest and too few positional changes can also cause atelectasis. During auscultation, atelectasis will sound like small popping noises.

Course crackles are similar to fine crackles but lower in pitch and louder (Bohadana et al., 2014). These noises indicate more severe diagnoses, such as pulmonary edema and chronic bronchitis.

Pulmonary edema is when the alveoli become filled with fluid, impairing gas exchange. Course crackles are the sound of the fluid moving during breathing. This can occur as a result of illness processes like hypertension and chronic kidney disease.

Bronchitis is inflammation of the bronchi. A viral infection causes acute bronchitis, usually starting in the upper airway and moving into the lungs. Chronic bronchitis is a part of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, which is caused by smoking cigarettes.

Pleural rub is a grating or rubbing sound that occurs when the pleural surfaces are inflamed and rubbing against each other (Bohadana et al., 2014). The pleura is the tissue surrounding the lungs, lining the chest cavity. For example, the tissue around the lungs is called the parietal pleural, and the ribs are covered by the visceral pleura. When these tissues get inflamed, it is called pleurisy. This can occur due to infections like pneumonia or a disease process like pulmonary embolism.

An embolus (moving blood clot) occurs when a thrombus (stationary blood clot) is transferred through the circulatory system from another part of the body. Once the embolus travels into an artery or vein that is too small, it will cause an obstruction. A pulmonary embolism is when the embolus gets trapped in the lung’s circulatory system. A cardiac embolism that enters the heart’s circulatory system will cause a myocardial infarction (heart attack).

This video shows some normal and abnormal lung sounds explained above (Geeky Medics, 2018b).

Auscultation of the Small and Large Intestines

Anatomy and Physiology of the Gastrointestinal Tract

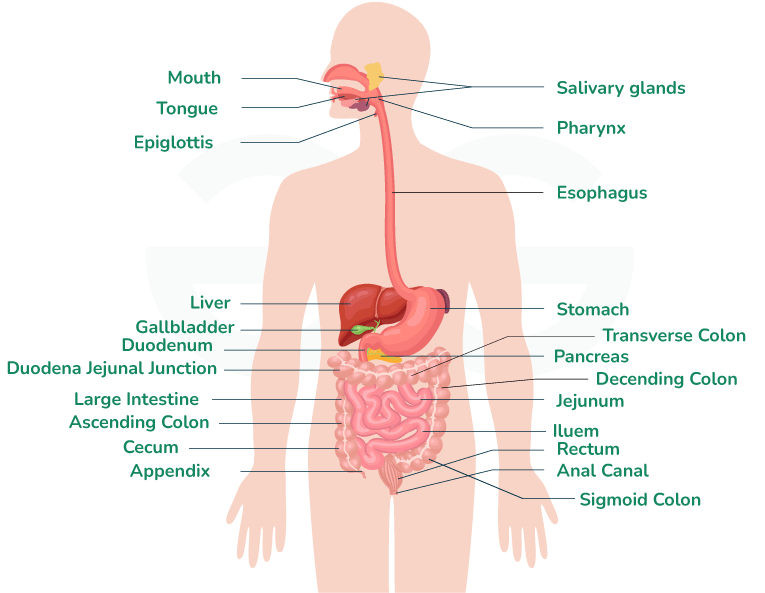

The gastrointestinal tract begins at the mouth and continues through the esophagus, the stomach, and the intestines. The intestines are made up of the small and large intestines. The small intestine comprises the duodenum, the jejunum, and the ileum. The large intestine contains the caecum (with the appendix), the colon (ascending, transverse, descending, and sigmoid colon), the rectum, and anus. The intestines, or the bowels, are one long muscular tube that digests and creates peristalsis (moves ingested food through the body). Many other organs are involved in food digestion (e.g., pancreas, gallbladder, etc.); however, this section will only focus on the bowels. We will focus on auscultating the abdomen’s anterior (front) aspect.

Diagram of the anatomy of the gastrointestinal tract (GeeksforGeeks, 2024).

Location of Auscultation

The peritoneal cavity (abdomen) houses most gastrointestinal organs and is sectioned into four quadrants and nine regions. These are essential to assess gastric motility after surgeries like a bowel resection or appendectomy.

These are the four quadrants of the peritoneal cavity (OpenStax, 2013).

The four quadrants are the lower right quadrant (LRQ), upper right quadrant (URQ), left upper quadrant (LUQ) and lower left quadrant (LLQ). Food moves from the small intestine into the large intestine in a clockwork motion (starting at the right lower quadrant). The lower right quadrant has the ileum, caecum, appendix, and beginning of the ascending colon. The upper right The upper left quadrant houses the end of the ascending colon and the beginning of the transverse colon, the liver, and the gallbladder. The lower left quadrant houses the end of the descending and sigmoid colon, the bottom of the stomach, and the pancreas. Auscultation is performed in all quadrants, starting with the lower left quadrant and following the path of gastric motility. During an assessment, auscultation of the abdomen must be done before touching the patient in that area. Percussion and palpation (light and deep) can cause a change in gastric sounds heard. These other assessment techniques will be discussed in another post.

These are the nine regions of the peritoneal cavity (OpenStax, 2013).

There are nine regions on the abdomen. The right hypochondriac, lumbar, and inguinal regions are on the right side of the abdomen. The middle has the epigastric, umbilical, and hypogastric or pubic regions. Just as on the right side, the left also has the hypochondriac, lumbar, and inguinal regions. The right inguinal region has the beginning of the ascending colon, caecum, and appendix. The right lumbar (middle back, between cervical vertebrae L1 to L5) region has the ascending colon and the beginning of the transverse colon. The right hypochondriac (under the ribs and cartilage) region houses the right side of the liver. The epigastric (above the stomach) region is the top of the stomach, liver, and gallbladder. The umbilical (umbilicus or bellybutton) region is the bottom of the stomach, the middle section of the transverse colon, and the small intestine’s top portion. The hypogastric (below the bowels) or pubic (pelvis) region has the bottom of the small intestine, the rectum, and the genitourinary organs (i.e., bladder, uterus, etc.). The left hypochondriac region has the top portion of the stomach and the pancreas. The left lumbar region has the descending colon. The left inguinal region has the sigmoid colon.

Normal Bowel Sounds

Peristalsis is the normal gastrointestinal tract movement (gastric motility). Upon auscultation, this sounds like the gurgling of fluid and gas in the abdomen. Auscultation should be performed in each quadrant during a routine assessment for at least one minute each.

Borborygmi is the rumbling sound of gas in the stomach and intestines. This can be increased or decreased depending on several factors, such as time since the last meal and diet, and varies from person to person. Sometimes, these sounds are very loud and can be heard audibly without a stethoscope.

Here is a video showing normal bowel sounds (A., 2022).

Abnormal Bowel Sounds

Hypermotility is increased bowel sounds. This is louder and more frequent than borborygmi and can be heard in patients with diarrhea and the early stages of a bowel obstruction.

Diarrhea occurs when the feces that are excreted are in liquid form rather than solid. The fluid moves through the colon so quickly that there are hypermotility sounds upon auscultation. Diarrhea can be caused by several factors, such as diet (e.g., liquids only), intolerances (e.g., Celiac disease), or medications (e.g., laxatives).

Bowel obstructions can be caused by disorders (e.g., constipation, Crohn's disease), tumours (e.g., cancer), or fecal impaction. In the area before the obstruction, the bowels will try to move the obstruction by increasing motility. There would also be hypomotility or an absence of sounds after the area of the obstruction.

Hypomotility is reduced motility sounds. This will occur in patients with constipation and bowel obstructions.

Constipation is bowel dysfunction that makes fecal material hard and difficult to excrete. This can be caused by factors like diet (e.g., low fibre, dehydration), bowel obstructions, and medications (e.g., laxative abuse).

Absent bowel sounds indicate a complete stoppage of peristalsis. Auscultation must be done for three minutes straight in all areas to ensure there are no bowel sounds. This can occur as a result of an ileus or late-stage bowel obstruction.

Ileus is the failure of peristalsis and, therefore, the absence of bowel sounds. It can be caused by laparotomy or peritoneal inflammation (Ferguson, 1990). Ileus can also result from infection (e.g., gastroenteritis) or syndromes (e.g., appendicitis). Factors like these can cause peritoneal inflammation and require surgery. Anesthesia is known to cause reduced peristalsis. When this is combined with surgical incisions through the bowel muscles, there is the possibility of nerve damage and absent bowel sounds.

Crepitus is the sound of air in cavities that should not be in. It sounds like popping or crunching noises. The peritoneal cavity is filled with fluid to ensure that the internal organs stay healthy and are protected. If air enters into the cavity, there is also a disruption in sterility. There are many causes for this, such as trauma (e.g., penetrating stab wounds) and infection (e.g., gas gangrene) (Ferguson, 1990).

Subcutaneous emphysema is when gas (air) leaks into a cavity (subcutaneous tissue in the skin) without air. This can occur all over the body. Some examples are seen in the lungs (pneumothorax or collapsed lung) and the esophagus (esophageal rupture from profuse emesis or vomiting).

Rubs (similar to the pleural rub in lung auscultation) can be heard over the liver, spleen, or if there is a mass in the abdomen (Ferguson, 1990). Abdominal masses can be attributed to cancers (e.g., bowel, spleen, liver, etc.), fibroids, aortic aneurysms (widening), etc.

Bruits are swishing sounds of the heart over major arteries in the abdomen (i.e., aorta, renal, and iliac arteries). This will be discussed in the section about auscultation of arteries and veins.

Auscultation of the Heart

Anatomy and Physiology of the Heart

The human heart is a fascinating organ. The heart’s function is to pump oxygenated blood through the arteries to the rest of the body. The heart is made up of three layers of muscle. called the endocardium, myocardium, and pericardium. The chambers and valves in the heart are made of endocardial tissue (endocardium). The heart muscles that pump blood are the myocardium. The pericardium is the “sac” surrounding the heart within the pericardial cavity. The heart pumps blood during systole and fills with blood during diastole. This is where the terms systolic and diastolic come from when discussing blood pressure.

A diagram of the heart’s anatomy (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 2022).

Circulation of blood through the heart (A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia, 2022).

Unoxygenated blood (blue on the diagram above) comes from the peripheral capillaries, through the veins and into the superior and inferior vena cava. The superior vena cava gets all the blood from the jugular (head and neck) veins, while the inferior vena cava receives all the blood from the body. The blood goes into the heart and the right atria during systole. Then, during diastole, the blood passes through the tricuspid valve and into the right ventricle. The right ventricle pushes the blood (systole) through the pulmonary valve and into the lung circulation for gas exchange. The oxygenated blood (red on the diagram above) comes from the lungs and enters the left atria during systole. Again, the blood is moved through the mitral valve into the left ventricle during diastole. Lastly, the oxygenated blood gets pumped into the aorta through the aortic valve and gets distributed around the body. The aorta splits into the carotid (head) and other major arteries, disseminating it through the smaller arteries and into the capillaries.

The heart is the main part of the circulatory system, but it also has its own circulatory system to keep it functioning.

Diagram of the coronary arteries and veins (P., 2017).

If one of these arteries becomes blocked by an embolus (blood clot), the tissue below it starts to necrose (die) from lack of blood flow. Necrosis of the tissue is what causes a myocardial infarction (heart attack). Depending on where the blockage is in the tissues, it can affect different tissues and cause different heart problems after the attack.

Location of Auscultation

Just like the lungs, the heart is encased within the thoracic cavity behind the ribs. There are four major areas to auscultate on the chest to hear the different valves of the heart: aortic, tricuspid, mitral, and pulmonic. There is a fifth point to auscultate on the heart called Erb’s point. All assessments should include cardiac auscultation, as it is the most important organ in the human body.

Here are the locations of auscultation of the heart on the anterior chest (Italiano, n.d.).

The aortic area can be heard between ribs two and three on the right side of the sternum (chest bone). The tricuspid valve (between the right atria and ventricle) can be heard between ribs five and six on the left side of the sternum. The pulmonic valve, where the blood gets pushed into the lungs for oxygenation, can be heard between the second and third ribs on the left side of the sternum. The mitral valve (between the left atria and ventricle) can be heard at the apex of the heart. The apex is the “tip” of the heart and the point where the heartbeat can be heard the loudest. Healthcare workers will auscultate the heart and lungs at the same time. The best location to hear both S1 and S2 sounds is called Erb’s point (between the third and fourth rib on the left side of the sternum).

Normal Heart Sounds

Heart sounds upon auscultation are created by the blood flowing through the cardiac valves and chambers. The heart usually makes two noises per heartbeat cycle, called S1 and S2, which sounds like “lub-dub” on auscultation.

S1 sounds or “lub” is the sound of the tricuspid and mitral valves closing occurring during systole. The louder component of the S1 sound is the mitral valve closing (Dornbush & Turnquest, 2023).

S2 sounds or “dub” is the aortic and pulmonic valves closing during diastole. The louder component of S2 is the pulmonic valve closing (Dornbush & Turnquest, 2023).

Laminar flow describes a smooth flow of blood with low resistance. This can be affected by the viscosity of the blood and the diameter of the tissue through which the blood flows (Dornbush & Turnquest, 2023). When the patient is in a resting position, laminar flow should be heard.

Turbulent flow is the opposite of laminar flow. It sounds rough as it has a high resistance caused by tissue narrowing or increased blood velocity (e.g., increased heart rate or blood pressure) (Dornbush & Turnquest, 2023).

Abnormal Heart Sounds

Systolic murmurs occur during systole (S1).

Ejection murmurs are “crescendo-decrescendo” sounds caused by blood flowing through an obstruction (Dornbush & Turnquest, 2023). Examples of obstructions include aortic or pulmonic valve stenosis (hardening or narrowing of the valve), ventricular septal defect (hole in the heart), and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (thickening of the muscle).

Regurgitation murmurs sound harsh and loud and completely cover up the sounds of S2 (Dornbush & Turnquest, 2023). These are caused by mitral and tricuspid insufficiency. The noise is a result of the regurgitation of blood back through the valve that is incompetent. Some of the blood that is being ejected will leak back through the valve and back into the ventricle.

Systolic clicks are loud noises that occur during systole. These occur because of a prolapse of the mitral or tricuspid valves into the atria when the ventricles are contracting (Dornbush & Turnquest, 2023).

Diastolic murmurs are murmurs that occur during diastole (S2).

Stenosis of the tricuspid and mitral valves (see ejection murmurs above) can also cause extra sounds to be heard on auscultation during diastole

Regurgitation murmurs of the aortic and pulmonic valves (see regurgitation murmurs above) can also cause adventitious sounds during diastole.

S3 sounds are extra noises caused by conditions (e.g., heart failure) that increase left atrial volume or ventricular filling pressure (Dornbush & Turnquest, 2023). This low-frequency early diastolic sound can be heard best at the apex of the heart. S3 has also been found in healthy children and adults.

S4 sounds are an occurrence of turbulent blood flow from an uncompliant ventricle. The sound comes from the atria pushing the blood into a stiffened ventricle (e.g., ventricular hypertrophy).

Patent ductus arteriosus sounds “machine-like” and is a continuous noise present at the upper area left of the sternum close to the pulmonic valve (between ribs two and three) (Dornbush & Turnquest, 2023). This is a connection between the pulmonary artery and the aorta. This is needed during fetal development and normally closes after birth. If the duct remains after birth, the pulmonary artery will regurgitate into the aorta. This can only be remedied with surgical intervention.

This video shows some normal and abnormal heart sounds (Geeky Medics, 2018a).

Auscultogram (Phonocardiogram)

An auscultogram or phonocardiogram is a visual representation of heart sounds. It allows for the detection of murmurs that cannot be heard with auscultation alone. It is used to help medical students study different cardiac diagnoses. It has also been found useful as a noninvasive technique to detect cardiac abnormalities of fetuses in utero.

Here is an example of a auscultogram or phonocardiogram of normal and abnormal heart sounds (Wikimedia, 2021).

Auscultation of Arteries and Veins

Anatomy and Physiology of the Circulatory System

The systemic circulation provides oxygenated blood from the heart to the tissues and organs in the rest of the body. Arteries distribute oxygenated blood to the body, while the veins return the unoxygenated blood to the heart. Below is a brief overview of the systemic circulatory system, and the following sections will focus solely on arteries and veins used in auscultation.

Diagram of the major arteries and veins in the circulatory system (Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2010).

The ascending aorta splits into the right and left carotid and subclavian arteries. The carotid arteries bring blood into the head and neck, while the subclavian arteries carry the blood to the upper limbs. The arms have many major arteries, like the axillary (armpit), brachial (upper arm), radial and ulnar (forearm). The descending aorta branches downward into the thoracic and abdominal cavities. There are many branches into the thoracic cage (intercostal), to the organs (celiac, renal, mesenteric, iliac, etc.), and the lower body (femoral, tibial, popliteal, etc.). All of the arteries have matching veins with the same names that bring the blood back to the heart. One exception to this is the carotid artery counterpart, which is the jugar vein in the neck.

Location of Auscultation

Some of the sounds auscultated in the systemic circulation can radiate from the heart and could be a cardiac issue. Sometimes, the arteries and veins are auscultated independently if there is an indication. However, most of the time, this auscultation is done while taking manual blood pressure.

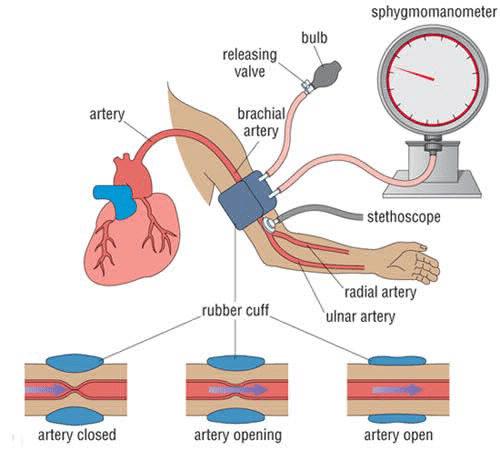

Blood Pressure

Blood pressure measures how much pressure the blood is being pushed into the circulation by the heart. It measures two numbers: the systolic and the diastolic. The average blood pressure for an adult is aimed at 120 over 80 millimetres of mercury (120/80 mmHg). Nowadays, it is commonly taken by a machine. However, every nurse learns how to do a manual blood pressure with a stethoscope and sphygmomanometer (“blood pressure cuff”).

Diagram of the manual blood pressure setup (Polat, 2019).

The nurse will place the stethoscope’s diaphragm on the antecubital fossa (space between the upper and lower arm) over the bottom of the brachial artery. With the cuff around the bicep, the cuff is inflated with air until the pulse is no longer heard. Then, the cuff is slowly deflated until the pulse is heard again upon auscultation. When the pulse returns, it is turbulent and pulsatile. This is called the Kortokoff sounds. The sounds will no longer be heard as the blood flow returns to normal.

Normal Sounds

There are five phases of sounds heard during a blood pressure reading (Korotfkoff sounds) that occur after the cuff is fully inflated.

Visual representation of Korotkoff sounds during blood pressure (Alkhair, 2017).

Phase one (I) is a faint tapping sound heard with the gradually deflating cuff; phase two (II) is the blowing or swishing sound that occurs when the blood flow is returning; phase three (III) is when the sharp pounding sound returns; phase four (IV) is the muffled flow turning into blowing again; and phase five (V) is the absence of sounds (Rehman & Hashmi, 2022). The systolic blood pressure is measured at the number indicated on the sphygmomanometer when the blood flow returns to the arm and the first tapping sound is present (Korotkoff sound, phase three). The diastolic blood pressure is measured at the time when the sound becomes quiet again (Korotkoff sound, phase five).

Abnormal Sounds

Bruits can be heard over the carotid arteries in the neck and have a turbulent flow. Unlike hums, this sound is loudest during systole and does not go away. Bruits in an artery can be caused by stenosis (hardening) or vascular occlusion (obstruction or compression) (Kurtz, 1990).

Hums are a continuous whining or roaring noise through systole and diastole (Felner, 1990). This can be heard in the jugular and subclavian veins and may be found in healthy individuals. These can be heard upon compression of the veins.

Here is a video demonstrating all five phases of Korotkoff sounds during a blood pressure assessment (Ausmed, 2020).

This overview of auscultation provides a look into auscultation and one of the most basic skills every nurse uses daily (or even hourly). Please comment about what you learned, ask a question, or leave feedback. I look forward to creating an educational environment for all nerds like me!

– V. A. Cyr

References

A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia. (2022) Circulation of blood through the heart

[Image]. National Library of Medicine. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/imagepages/19387.htm

A., M. [@mem00010] (13 September, 2022). Normal bowel sound [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iV_skr-El4w

Alkhair, S. (2017). Korotkoff Sounds five phases [14] [Image]. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/figure/7-Korotkoff-Sounds-five-phases-14_fig6_314238585

Ausmed. (19 March, 2020). Blood Pressure: Korotkoff Sounds | Ausmed Explains… [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K4ftef-SY94

Bohadana, A., Izbicki, G. & Kraman, S. S. (2014). Fundamentals of lung auscultation. New England Journal of Medicine, 370(8), 744-751. 10.1056/NEJMra1302901

Brady, M. F. & Burns, B. (2023). Airway Obstruction. StatPearls. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470562/

Choudry, M., Stead, T. S., Mangal, R. K. & Ganti, L. (2022). The History and Evolution of the Stethoscope. Cureus, 14(8), e28171. 10.7759/cureus.28171

Dornbush, S. & Turnquest, A. E. (2023). Physiology, Heart Sounds. StatPearls. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541010/

Ekomaru, C. (2020). The points of auscultation for the front (left) and back (right) [Image]. 3D4Medical. https://3d4medical.com/blog/auscultation-of-the-lungs

Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc. (2010). Human circulatory system [Image]. Britannica.

https://www.britannica.com/science/circulatory-system/images-videos

Felner, J. M. (1990). Chapter 7: An Overview of the Cardiovascular System. In Walker, H. K., Hall, W. D., Hurst, J. W. Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations, 3rd ed. Boston: Butterworths. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK393/

Ferguson, C. M. (1990). Chapter 93: Inspection, Auscultation, Palpation, and Percussion of the Abdomen. In Walker, H. K., Hall, W. D., Hurst, J. W. Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations, 3rd ed. Boston: Butterworths. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK420/

GeeksforGeeks.(2024). Gastrointestinal Tract Diagram [Image]. https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/gastrointestinal-tract-diagram/

Geeky Medics. (28 February, 2018a). Heart murmur sounds (cardiac auscultation sounds) | UKMLA | CPSA [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q5-0mSydRR4

Geeky Medics. (7 March, 2018b). Lung sounds (respiratory auscultation sounds) | UKMLA | CPSA [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2NvBk61ngDY

Grover, S., Mathew, J., Bansal, A. & Singhi, S. C. (2011). Approach to a Child with Lower Airway Obstruction and Bronchiolitis. Indian Journal of Pediatrics, 78(11), 1396–1400. 10.1007/s12098-011-0492-z

Italiano, C. (n.d.) Cardiac auscultation [Image]. Gastropato. https://www.gastroepato.it/en_auscultazione_cuore.htm

Kurtz, K. J. (1990). Chapter 18: Bruits and Hums of the Head and Neck. In Walker, H. K., Hall, W. D., Hurst, J. W. Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations, 3rd ed. Boston: Butterworths. : https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK289/

Littmann. (n.d.). Littmann Classic III Stethoscope: Black 5620 [Image]. Stethescope.com. https://stethoscope.ca/products/littmann-classic-iii-stethoscope-black-5620?_pos=1&_sid=26c25d9b4&_ss=r

Littmann. (n.d.). 3M™ Littmann® CORE Digital Stethoscope [Image].

https://www.littmann.ca/3M/en_CA/p/d/b5005222000/

Medicosage. (n.d.). Stethoscope | Parts, Uses, Method, Types, How to Buy [Image]. https://medicosage.com/stethoscope-parts-uses-method-types-how-to-buy/

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (2022). How the Heart Works - What the Heat Looks Like [Image]. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/heart/anatomy

OpenStax. (2013). There are (a) nine abdominal regions and (b) four abdominal quadrants in the peritoneal cavity [Image]. In Wikimedia Commons, The Free Media Repository. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Abdominal_Quadrant_Regions.jpg

P. M. (2017). What is coronary circulation? [Image]. Socratic Q&A. https://socratic.org/questions/what-is-coronary-circulation

Pokusai, O. (n.d.). Lung anatomy structure scheme diagram schematic raster illustration. Medical science educational illustration [Image]. Adobe Stock Images. https://stock.adobe.com/search/images?k=lungs+diagram&asset_id=652265771

Polat, K. (2019). Non-invasive blood pressure measurement [Image]. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/figure/a-Non-invasive-blood-pressure-measurement-b-Invasive-blood-pressure-measurement-a_fig1_332108059

Rehman, S. & Hashmi, M. F. (2022). Blood Pressure Measurement. StatPearls. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482189/

Roguin, A. (2006). Rene Theophile Hyacinthe Laënnec (1781–1826): The Man Behind the Stethoscope. Clinical Medicine & Research, 4(3), 230—235. 10.3121/cmr.4.3.230

Science Museum Group. (n.d.). Cammann binaural stethoscope, presented by Cammann to Dr. Barth [Image]. https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co90885/cammann-type-binaural-stethoscope-stethoscope

Science Museum Group. (n.d.). Laennec stethoscope made by Laennec, c.1820 [Image]. https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co90986/

Unknown. (n.d.). Medical diagnostic device stethoscope or phonendoscope [Image]. Vecteezy. https://www.vecteezy.com/vector-art/3423043-medical-diagnostic-device-stethoscope-or-phonendoscope

Van Leest Antiques. (n.d.). Piorry stethoscope, C 1830 [Image].

https://www.vanleestantiques.com/product/piorry-stethoscoop-c-1830/

Veiga, P. (2009). Papyrus Ebers, Leipzig University [Image]. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Papyrus-Ebers-Leipzig-University-http-digiubuni-heidelbergde-diglit-ebers1875bd1_fig2_215521596

Wikimedia. (2021). Phonocardiograms from normal and abnormal heart sounds [Image]. In Wikimedia Commons, The Free Media Repository. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Phonocardiograms_from_normal_and_abnormal_heart_sounds.svg

Wikipedia. (March 23, 2024). Auscultation. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Auscultation

Wilks, S. (1883). Evolution of the stethoscope [Image]. Popular Science, 22(28), 490. https://books.google.ca/books?id=FSsDAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA490#v=onepage&q&f=false

Comments