A History of Wound Care

- V. A. Cyr

- Jan 22, 2025

- 15 min read

Wounds are a typical day occurrence for everyone, from paper cuts and knee scrapes to knife wounds and amputations. What was used in ancient times to protect wounds and prevent infection? How is beer and wine related to wound care? This topic will discuss different types of wounds like pressure ulcers, surgical incisions, and burns. We will also discuss the origins of wound care and how it has evolved over time. This post will look into modern-day wound treatment techniques, such as the sterile technique. This post does not include any real-life photos of wounds, only diagrams to describe the different processes involved in wound care.

Definitions & Types

Skin

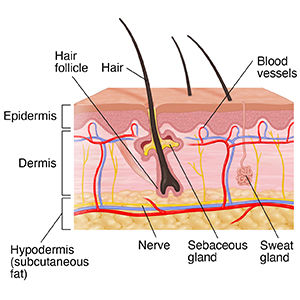

The skin, or the integumentary system, is the body’s first defence against injury and infection. The skin is made up of multiple layers containing different structures.

Epidermis

The epidermis comes from the words epi (meaning “on” or “above”) and dermis (meaning “skin”). It is the visible outer layer of the skin. This layer also has melanocytes, which are the cells that create melanin and give the skin its colour.

Dermis

The dermis is the layer of skin beneath the epidermis. It contains blood vessels, nerves, hair follicles, sebaceous glands (which produce oil called sebum), and sweat glands.

Hypodermis

The hypodermis (hypo meaning “under” or “below”) is also called the subcutaneous (SQ or SubCut) layer. This layer encompasses fat, which helps the body preserve heat and protects the internal structures from damage.

Here is a diagram showing the layers of the skin and their structures (Johns Hopkins Medicine, n.d.).

Types of Wounds

Open Wounds

An open wound is any injury that breaks open the skin. These include incisions (cuts made by a sharp object, e.g., surgical incision), abrasions (superficial friction marks, e.g. road rash), lacerations (skin is overstretched, e.g., cut from broken glass), and punctures (a wound that makes a hole in the skin, e.g., vaccine mark or insect bite). The complication with open wounds is the higher risk of infection because of the breach in the skin layers. Bacteria can enter the bloodstream through an open wound and need to be treated as soon as possible.

Different types of open wounds (Lecturio Nursing, 2024).

Closed Wounds

Closed wounds are injuries that occur underneath the epidermis layer of the skin. Examples of closed wounds are contusions (bruising), hematomas (damage to blood vessels), and crush injuries (high-force injury, e.g., car crash, broken bones that do not break through the skin). Although the risk for infection is lower with closed wounds, these can be much more lethal as the extent of the injury is not as evident. For example, someone with internal abdominal bleeding after a car accident may not show any signs of symptoms until they decompensate, versus someone who has a visible leg injury. Properly assessing injuries is essential to triage patients appropriately.

Some examples of closed wounds (Lecturio Nursing, 2024).

Pressure Ulcers

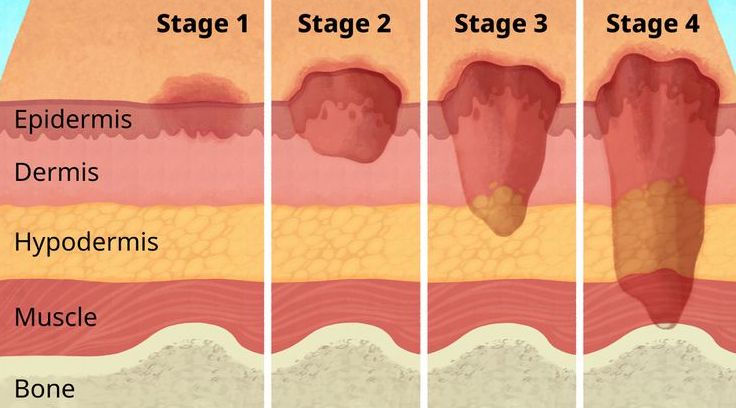

Pressure ulcers, also known as pressure injuries or bedsores, are localized skin and soft tissue injuries that develop due to prolonged pressure exerted on an area of the body (Zaidi & Sharma, 2024). Pressure ulcers can develop in as little as two hours, so position changes throughout the day and night are essential. There are four main stages of a pressure injury.

Stage 1 occurs when the skin is intact but has erythema (redness) that is non-blancheable (the skin does not go white when pressed).

Stage 2 is a partial-thickness skin injury involving the epidermis and dermis.

Stage 3 is a full-thickness injury to the skin that extends into the subcutaneous tissue. A foul odour, slough (dead skin tissue), or eschar (dead tissue that forms a scab-like covering) may be visible in the wound bed.

Stage 4 is a full-thickness skin loss that foes through the fascia past the subcutaneous tissue. This considerable tissue loss can also involve muscles, bones, tendons, and joints.

Unstageable describes pressure ulcers where the depth is unknown due to the amount of slough or eschar obscuring the tissue damage. Debridement (cleaning) is needed to assess the extent of the injury fully.

The four stages of a pressure ulcer (Giorgi, 2023).

Wound Classification

Wounds are typically defined into two categories: acute and chronic, which are then classified depending on the type of injury.

Acute Wounds

Acute wounds are usually done quickly and heal normally. Examples of acute wounds are injuries from traumatic injury and surgical incisions. Assessment of an acute wound includes how and when the injury occurred, the involvement of underlying structures (e.g., nerves, muscles, bones, etc.), and the likelihood of infectious contamination (Nagle et al., 2023).

Open Fractures

The Gustillo-Anderson Classification System is an example of wound classification for open fractures (bone fractures in which the skin is broken, usually caused by a high-velocity impact such as a motor vehicle accident).

Type I is a wound with clean skin opening less than 1cm, minimal tissue damage, minimal muscle contusion (bruise), and 0-2% risk of infection.

Type II is a laceration over 1cm, more extensive soft tissue damage, minimal to moderate crushing of bone, minimal comminution (splinters), 2-5% risk of infection.

Type III has extensive tissue damage to muscles, skin, and nerves, as well as high-energy injury with crushing components.

Type IIIA has extensive laceration, adequate bone coverage, segmental fractures, and a 5-10% risk of infection. Examples include gunshot wounds, farm injuries and amputations.

Type IIIB is also extensive but requires soft tissue flap closure and usually has massive contamination with a risk of infection at 10-50%.

Type IIIC is the same extent as Type IIIB but has a vascular injury requiring repair, and the risk of infection is about 25-50%.

Stages I to IIIC of the Gustillo-Anderson classification system (Ortego, 2016).

Surgical Wounds

The Surgical Wound Classification (SWC) divided surgical wounds into four classes with a score of post-operative risk infection of a surgical site (SSI).

Class 1 Wounds are classified as “Clean.” There are no signs of infection, the skin is closed, and if a drain is required, it is a closed drainage system (Herman et al., 2023). Examples include wounds made for inguinal (groin) hernia repairs and thyroidectomies (removal of the thyroid gland).

Class 2 Wounds are “Clean-contaminated.” These have a low level of contamination and can involve respiratory, gastrointestinal, genital and urinary tracts (Herman et al., 2023).

Class 3 Wounds are classified as “Contaminated.” These can be from a breach in sterile technique or a leak in the gastrointestinal tract.

Class 4 Wounds are considered “Infected” or “Dirty.” These wounds result from inadequate treatment of traumatic wounds, gross purulence (accumulation of pus), and evident signs of infection (Herman et al., 2023). This can occur in surgeries when an internal organ is perforated, and complete sterilization of the area is difficult to achieve.

Chronic Wounds

Chronic wounds have a delayed healing period due to other factors. These wounds can start as an acute wound and have difficulty healing or result from an underlying condition. These include poor circulation, weakened immune system, diabetes, the size of the wound, and pressure exerted on the wound. Examples of chronic wounds are pressure ulcers (see above) and burns.

Factors Affecting Healing

Poor circulation can include peripheral artery disease (arteries become narrow) and venous insufficiency (enlarged veins and varicose veins) (Informed Health, 2022). This is common in the extremities of older adults, especially the legs. Impaired blood perfusion to the wound does not allow enough oxygenated blood to access the wound to help heal. Conditions like anemia (lack of oxygen in the blood) can also impact healing time. Diabetes mellitus occurs when the pancreas cannot produce enough or any insulin to control the blood’s glucose levels (Informed Health, 2022). This can lead to neuropathy (damage to the peripheral nerves) and loss of sensations. The problem with having nerve damage is there is a higher possibility of injury to that person’s extremities, and it can impair the blood flow to them as well. Having a weakened immune system is seen in people with chronic conditions like cancer, the elderly, and people with poor diets. The larger the wound size will affect the time of the healing process. Severe burns are an example of a chronic wound as it has a large amount of tissue destruction, which can be in a small area but deep or around the entire body. Mechanical pressure on the wound will inhibit healing, so pressure ulcers are chronic and complex to heal.

Burns

Burns can be caused by heat (e.g., fire, smoke), electricity (e.g., lighting), radiation, chemicals (e.g., acids), or friction. They are separated into categories or degrees depending on the thickness into the skin.

Superficial Thickness (First Degree) Burns only involve the epidermis. They cause pain and erythema (redness) but do not blister or scar.

Partial or Intermediate Thickness (Second Degree) Burns extend into the deeper parts of the epidermis and sometimes into the dermis. The more superficial these burns, the more painful and blistering (fluid-filled bubble) they will be. The deeper the burn goes into the dermis, the less pain will be present, but there is a higher risk of infection and scarring.

Full Thickness (Third Degree) Burns go through the entire epidermis layer. These wounds are dry with no formation of blisters. There is no pain with these burns as the nerves have been destroyed in the area. These wounds will take longer to heal with significant scarring and risk of infection and contracture (shortening of tissues causing limited range of motion). These wounds will need skin grafting to recover and fully increase the limb’s function.

Fourth Degree Burns involve the muscle or bone under the skin. These burns usually lead to the amputation of the affected limb or removal of the tissue in the area, as there is no longer any blood flow to aid healing.

Diagram of the types of burns (Jeschke et al., 2020).

The Rule of 9s is a tool used to estimate the area of the body affected by burns. The diagram shows the body separated into nine regions: the head, the torso, the right arm, the left arm, the right leg, the left leg, and the groin. These areas are on the anterior (front) and posterior (back of the body); all percentages add up to 100%. Depending on where the person is burnt, they add up the areas affected and estimate the severity of the wound.

The Rules of 9s to estimate burns in an adult (Kim et al., 2022).

Healing

Stages of Healing

Hemostasis happens immediately after the wound occurs. The damaged blood vessels bleed, and the body reacts by causing vasoconstriction to limit blood loss. Platelets and fibrin in the blood go to the wound site and start coagulating (forming a blood clot), which also helps inhibit blood loss (Wound Evolution, n.d.). This stage can last up to two days or longer.

Inflammation occurs once hemostasis is complete. This process comprises vasodilation to begin healing the wound and prevent infection. Leukocytes (white blood cells) in the blood enter the wound site to clean bacteria that has entered through the skin. Inflammation is characterized by erythema (redness), swelling, pain, and heat around the wound (Wound Evolution, n.d.). This stage can sometimes occur simultaneously with hemostasis and lasts six days or longer.

Proliferation is defined by angiogenesis or the formation of granulation tissue. Granulation tissue is the new connective tissue and blood vessels replacing damaged skin (Wound Evolution, n.d.). Adequate blood and oxygen perfusion to the new tissue is vital for proper wound healing, which is evident when the tissue is pink. This stage can take more than two weeks to complete.

Maturation or Remodeling is when the skin uses collagen to recreate more durability and elasticity, forming a scar (Wound Evolution, n.d.). The scar tissue is about 20% weaker than un-injured skin (Wound Evolution, n.d.). This stage starts when the wound is closed and can last up to two years.

The four stages of wound healing (CK Birla Hospital, 2024).

Healing by Intention

Healing by Primary Intention is the technique of closing a wound that is uncontaminated and simple to close. This can be done using sterile sutures or synthetic adhesive materials (Salcido, 2017). This wound will heal into a scar with little to no complications. Examples are surgical incisions and paper cuts (Lecturio Nursing, 2024).

Healing by Secondary Intention can be used as a delayed primary closure staging technique for wounds that are too large to close easily (Salcido, 2017). Wound dehiscence is a complication of these problematic wounds and is when the wound separates further during healing. Dehiscence is common among wounds with high-margin tension (skin is too tight to be closed), in patients who are overweight, and in areas with frequent motion (e.g., knees, fingers, etc.) (Salcido, 2017). Examples include lacerations, burns, and ulcers (Lecturio Nursing, 2024).

Healing by Tertiary Intention occurs when a wound is deliberately left open after debridement (cleaning) of all tissue, impeding the healing process (Salcido, 2017). This would be done in the case of an infected and contaminated wound. The wound can be closed later once vital tissue is formed, and tissue perfusion (blood flow) is adequate (Salcido, 2017). Examples could be an animal bite or an avulsion (Lecturio Nursing, 2024). Techniques such as surgical skin flaps and vacuum-assisted closure machines help heal wounds of this severity.

This diagram shows the differences between healing by primary, secondary and tertiary intentions (Lecturio Nursing, 2024).

Origins

Anything wrapped to protect a wound can be called dressings, bandages, or plasters.

The term “plaster” comes from the ancient practice of putting mixtures of mud, clay, plants, herbs, and oil onto a wound (Shah, 2012). Beer was also used in ancient medicine; the Sumerians (5000-1800 BC) brewed at least 19 types of beer. A prescription from this time stated, “Pound together fur-turpentine, pine-turpentine, tamarisk, daisy, flour of inninnu strain; mix in milk and beer in a small copper pan; spread on skin; bind on him, and he shall recover.” (Shah, 2012).

One of the oldest mentions of medical knowledge is on a clay tablet from 2200 BC, describing the “three healing gestures” as washing the wound, making the plasters, and bandaging the wound (Shah, 2012). In Ancient Egypt, honey, grease (animal fat) and link (vegetable fibres) were used in wrapping wounds (Shah, 2012; Smith, 2015). Grease provides a barrier to bacteria, and honey is an antibacterial agent that prevents infection (Shah, 2012). In the Iliad (circa 1200 BC), Homer described 141 wounds and used 150 anatomical terms (Walker, 1990).

Depiction of Achilles taking care of Patroclus, wounded by an arrow from around 500 BC (IMSS, n.d.).

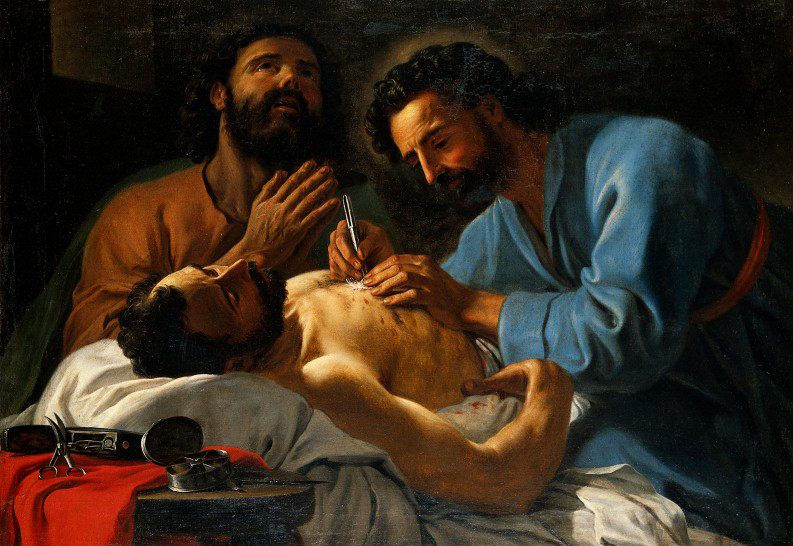

The Greek physician Hippocrates treated ulcers with wine and covered them with fig leaves (Smith, 2015). The Greeks stressed cleanliness and watching the wound with clean water, vinegar, and wine. A prescription from Hippocrates wrote: “For an obstinate ulcer, sweet wine and a lot of patience should be enough” (Shah, 2012).

Cosmas and Damian dressing a chest wound by Antoine de Favray in 1748 (Smith, 2015).

The 19th Century saw the Germ Theory, antiseptic technique and the introduction of antibiotics. In the mid-19th Century, Louis Pasteur studied microbiology, leading to the Germ Theory (Shah, 2012). In the 1860s, Joseph Lister used carbolic acid as an antiseptic on wounds (Shah, 2012). Robert Koch studies on aseptic technique and anesthesia revolutionized the world of surgical practices (Shah, 2012).

In the 1920s, Earle Dickson developed the first “band-aid” by attaching cotton to surgical tape to ensure the dressing stayed secure (Smith, 2015). He came up with this idea after his wife, a housewife who cooked a lot, got various cuts and burns and needed wound care (Smith, 2015). Johnson and Johnson took over the patent and began mass marketing Band-Aids. When the bandages were not selling as much as anticipated, they handed them free to Boy Scout troops across the United States (Smith, 2015). This free advertising for the company successfully brought parents of the troops into buying the Band-Aid brand bandages.

Earle Dickson’s patent for the first "band-aid" (Smith, 2015).

In the 20th century came the advent of modern wound healing. Most modern products include absorbent materials such as alginates and foam (Nakayama, 2018). An example was in 2008, when the US military began using QuikClot, a dressing infused with kaolin (an anti-coagulant) to help clot and prevent blood loss (Smith, 2015). Many therapies are used today to treat chronic wounds – some of these will be discussed in the next section. Other surgical interventions (e.g., skin grafts) will be investigated in the future!

Timeline Throughout History : Wound Dressing

Wound Care Techniques in Medicine

Sterile (Aseptic) Dressings

Sterile or aseptic technique is essential to ensure there is no introduction of bacteria into the wound during a dressing change. This should be observed in all dressing changes where the skin is broken, but especially in situations where the wound is at a higher risk of infection (e.g., VAC dressings, drains, PICC lines). This will be a quick overview of the sterile dressing technique used daily in the hospital for various wounds (e.g., surgical hip incisions, pressure ulcers, etc.).

A standard sterile wound care setup includes a sterile tray and gloves. There are specific steps to be taken to ensure there is no break in sterility (sterile field). There are “clean” forceps (“tweezers”) that are used to help open the tray and ensure nothing touches the inside sterile field. Inside the tray is some gauze, a tray for cleansing solution, a large dressing, and sterile forceps. The solution (normal saline or sterile water) is carefully added into the sterile field without wetting the field or the items, which is considered a break in sterility. Other sterile items are added into the sterile field without touching them (e.g., silver dressing, adhesive film dressing, cotton swabs, sterile ruler, etc.), either by letting them fall into the field un-aided or using the clean forceps provided. There is a small gap around the edge of the field where the clean forceps are placed, keeping the sterile end inside the field and the clean end outside.

An example of a sterile dressing tray setup (RainTree, n.d.).

The wound is prepped by removing the old dressing and cleaning any areas around the wound that are visibly dirty. This is done with clean gloves, and hand hygiene is performed after removing gloves.

Once the patient is ready and the sterile field is prepped, the sterile gloves must be donned before starting the dressing. They are packaged specifically to aid in the unique donning technique. The main idea is that the hands only touch the inside of the gloves, keeping the outside sterile. Once the gloves are on, the practitioner can only touch the sterile field. Any break in sterility would result in having to restart the sterile field from the beginning.

Donning the first sterile glove by touching the inside of the gloves only (BC Open Text, n.d.).

Donning the second glove by using the first gloved hand to touch the sterile side of the gloves (BC Open Text, n.d.).

Cleaning the wound involves using sterile gauze and solution to remove debris. This occurs in a “clean to dirty” motion (from cleanest area to dirtiest). The incision is cleansed first, then the outside of the wound is cleaned. The wound must be completely dry before applying the dressing.

Some examples of other materials used in dressings that could be prescribed to aid in healing include

Alginates, which dries exudate from wounds (Britto et al., 2024).

Hydrocolloids absorb exudate to prevent bacteria growth (Britto et al., 2024).

Antimicrobials use silver, which aids in preventing infection and decreases odour (Britto et al., 2024).

VAC Dressings

Vacuum-Assisted Wound Closure (VAC) dressings are a type of sterile dressing that uses negative-pressure therapy to heal a wound from the inside out. These are used in large chronic wounds like ulcers to drain excess fluid, help draw wound edges together, and improve blood flow (Johns Hopkins Medicine, 2025).

During the sterile setup, the practitioner will add all necessary items, including a special foam and adhesive film, to complete this dressing. The foam must be cut to be as close to the size of the wound. This can be difficult if the wound is odd or has tunnelling (a hole that burrows into the skin). Once the foam is correctly inserted and attached to the film, the tubing must be connected from the foam to the VAC machine. Testing is done to ensure there is a good seal. The dressing takes a lot of patience and practice to perfect and ensure sterility is kept throughout.

This is a diagram of the typical VAC setup (Yetman, 2020).

This is a really fun subject for most nurses! Some of the most complex cases include difficlut wound treatment. For exmaple, I have dealt with extensive complications from a hip surgery with deep tunneling requiring a VAC dressing that took 45 minutes to complete! What intesresting wounds have you seen or treated?

– V. A. Cyr

References

3M. (n.d.). 3M™ V.A.C.® Ulta 4 Therapy System [Image]. https://www.3m.co.uk/3M/en_GB/p/d/b5005265197/

BC Open Text. (n.d.). Insert hand into opening [Image]. https://opentextbc.ca/clinicalskills/chapter/sterile-gloving/

BC Open Text. (n.d.). Insert fingers [Image]. https://opentextbc.ca/clinicalskills/chapter/sterile-gloving/

Britto, E. J., Nezwek, T. A., Popowicz, P. & Robins, M. (2024). Wound Dressings. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470199/

CK Birla Hospital. (2024). Wound Healing [Image]. https://www.ckbhospital.com/blogs/what-are-the-stages-of-wound-healing/

Giorgi, A. (2023). How Different Stages of Pressure Ulcers Look

[Image]. https://www.verywellhealth.com/pressure-ulcer-7549469

Herman, T. F., Popowicz, P. & Bordoni, B. (2023). Wound Classification. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554456/

Informed Health. (2022). Overview: Chronic wounds. Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care(IQWiG). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK326431/

International Museum of Surgical Science (IMSS). (n.d). Wound Healing: Ancient Wisdom, Modern Technology [Image]. https://imss.org/wound/

Jeschke, M. G., van Baar, M. E., Choudhry, M. A., Chung, K. K., Gibran, N. S. & Logsetty, S. (2020). Burn injury [Image]. Nat Rev Dis Primers 6, 11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-020-0145-5

Johns Hopkins Medicine. (n.d.). Anatomy of the Skin [Image]. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/skin/anatomy-of-the-skin

Johns Hopkins Medicine. (2025). Vacuum-Assisted Closure of a Wound. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/treatment-tests-and-therapies/vacuumassisted-closure-of-a-wound

Kim, H., Shin, S., & Han, D. (2022). Review of History of Basic Principles of Burn Wound Management [Image]. Medicina, 58(3), 400. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina58030400

Lecturio Nursing. (2024). Types of Wounds & Classification [Images]. https://www.lecturio.com/nursing/free-cheat-sheet/types-of-wounds-classification/#cheatsheetdownload-regwall

Nagle, S. M., Stevens, K. A. & Wilbraham, S. C. (2023). Wound Assessment. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482198/

Nakayama, D. K. (2018). Antisepsis and Asepsis and How They Shaped Modern Surgery. American Surgery, 84(6), 766-771. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29981599/

Ortego, A. (2016). Open Fractures [Image]. Core EM. https://coreem.net/core/open-fractures/

QuikClot. (n.d.). QuikClot Combat Gauze® [Image]. https://quikclot.com/QuikClotProducts/QuikClot-Combat-Gauze.htm

RainTree. (n.d.). RainTree Dressing Set [Image]. https://raintreemedical.com/product/raintree-dressing-set-i/

Salcido, R. (2017). Healing by Intention. Advances in Skin & Wound Care, 30(6), 246-247. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ASW.0000516787.46060.b2

Shah, J. B. (2012). The History of Wound Care. Journal of the American College of Certified Wound Specialists, 19(3), 65-66. 10.1016/j.jcws.2012.04.002

Smith, E. (2015). Before the Band-Aid, People Used Honey and Sugar to Wrap Wounds. Atlas Obscura. https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/before-the-bandaid-people-used-honey-and-sugar-to-wrap-wounds

Smith, E. (2015). Cosmas and Damian dressing a chest wound, 1748, by Antoine de Favray [Image].https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/before-the-bandaid-people-used-honey-and-sugar-to-wrap-wounds

Smith, E. (2015). Earle Dickson’s 1929 patent for the band-aid [Image].https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/before-the-bandaid-people-used-honey-and-sugar-to-wrap-wounds

Smith, E. (2015). Variations of Band-Aid packaging from the 20th century [Image].https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/before-the-bandaid-people-used-honey-and-sugar-to-wrap-wounds

Theerman, P. (2014). Aseptic Surgery: Innovation circa 1900. NYAM History of Medicine & Public Health.https://nyamcenterforhistory.org/2014/09/08/aseptic-surgery-innovation-circa-1900/

Theerman, P. (2014). Sterile dressings. From Charles Truax’s The Mechanics of Surgery, ed. James M. Edmonson [Image]. https://nyamcenterforhistory.org/2014/09/08/aseptic-surgery-innovation-circa-1900/

Theerman, P. (2014). Sterilized gauze. From Charles Truax’s The Mechanics of Surgery, ed. James M. Edmonson [Image]. https://nyamcenterforhistory.org/2014/09/08/aseptic-surgery-innovation-circa-1900/

Walker, H. K. (1990). The Origins of the History and Physical Examination. Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations, 3rd ed. Boston: Butterworth. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK458/

Wound Evolution. (n.d.). The Four Stages of Wound Healing. https://www.woundevolution.com/blog/the-four-stages-of-wound-healing/

Yetman, D. (2020). What You Need to Know About Vacuum-Assisted Wound Closure (VAC) [Image]. Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/wound-vac#management

Zaidi, S. R. H. & Sharma, S. (2024). Pressure Ulcer. StatPearls[Internet].https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553107/

Comments